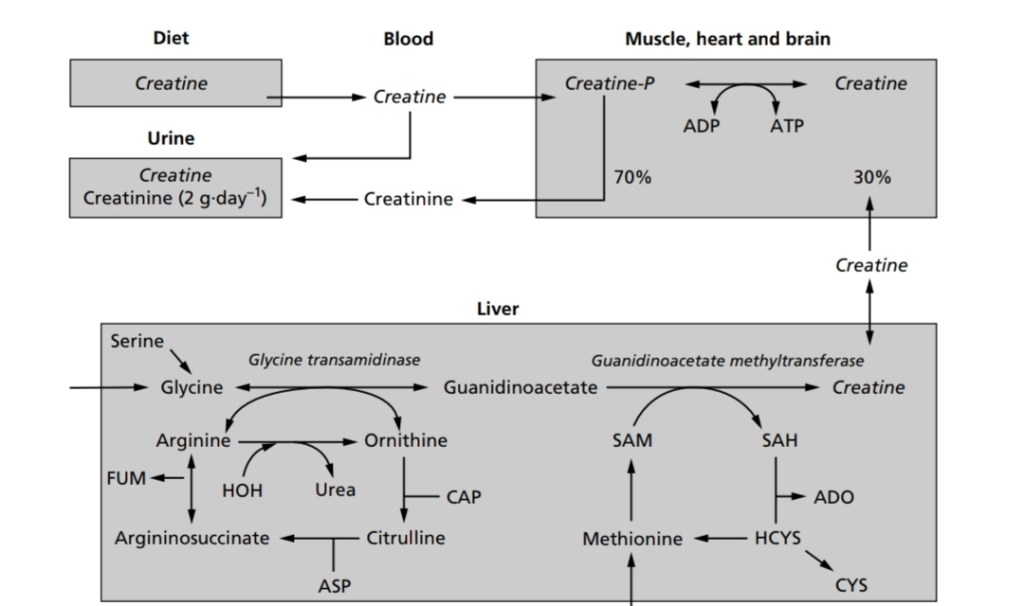

Creatine, or methyl guanidine-acetic acid, is a naturally occurring compound found in abundance in skeletal muscle. It is also found in small quantities in brain, liver, kidney and testes. In a 70 kg man, the total body creatine pool amounts

to approximately 120g, of which 95% is situated in the muscle.

In the case of humans, however, it is generally accepted that the majority of creatine synthesis occurs in the liver. As little creatine is found in the major

sites of synthesis, it is logical to infer that

transport of creatine from sites of synthesis to storage must occur, thus allowing a separation of biosynthesis from the utilization

As skeletal muscle is the major store of the body creatine pool, this is the major site of creatinine production. Daily renal creatinine excretion is relatively constant in an individual, but can vary between individuals being dependent on the total muscle mass in healthy individuals .Once generated, creatinine enters circulation by simple diffusion

and is filtered in non-energy-dependent

process by the glomerulus and excreted in urine.

If the muscle creatine concentration can be increased by close to or more than 20 mmol ·kg–1 dm. as a result of acute creatine ingestion, then performance during single and repeated bouts of maximal short-duration exercise will be significantly improved. However, the exact mechanism by which this improvement in exercise performance is achieved is not yet clear. The available data indicate that it may be related to the stimulatory effect that creatine ingestion has upon pre-exercise PCR availability, particularly in fast-twitch muscle fibres

PCr availability in type II fibres is generally accepted to limit exercise capacity during maximal exercise, the increase in type II muscle fibre PCR concentration as a consequence of creatine supplementation may have improved contractile function during exercise by maintaining ATP turnover in this fibre type.

It should be comprehended, however, that the positive effects of creatine supplementation on

muscle energy metabolism and function are also likely to be the result of the stimulatory effect that an increase in cytoplasmic free creatine will have on mitochondrial mediated PCr resynthesis

In conclusion, information relating to the

effects of dietary creatine ingestion on muscle function and metabolism during exercise in healthy normal individuals and in disease states is relatively limited. Based on recent findings, it would appear that it is important to optimize

tissue creatine uptake in order to maximize performance benefits, and therefore further work is required to elucidate the principal factors regulating tissue creatine uptake in humans.

More information is needed about the exact mechanisms by which creatine achieves its cryogenic effect and on the long term effects of creatine supplementation. With respect to this last point, it should be made clear that the health risks associated with prolonged periods of high-dose creatine supplementation are unknown; equally, however, research to date clearly shows it is not necessary to consume large amounts of creatine to load skeletal muscle. Creatine supplementation may be viewed as a method for producing immediate improvements to athletes involved in explosive sports. In the long run,creatine may also allow athletes to benefit from being able to train without fatigue at an intensity higher than that to which they are normally accustomed. For these reasons alone, creatine supplementation could be viewed as a significant development in sports related nutrition.

If you enjoyed this post don’t forget to like, share and comment! Follow my blog for similar content 😊

Sources and links:-

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/263269

https://www.verywellfit.com/creatine-what-should-you-know-about-it-89099